Perhaps the word “terroir” makes you think of soil, but that’s not quite true. Things are much more complex than they first appear.

In short, ‘terroir’ is a French term that encompasses the defining elements of a microclimate or wine-growing region. There are many definitions of it on the internet, and most of them touch on the influence of climate, soil, temperature, exposure, relief in a given wine country. You will also come across approaches from some proponents who believe that only natural factors contribute to the shaping of a terroir.

Personally, I belong to the other camp who, in addition to natural conditions, believe that human involvement plays a special role in defining terroir. To illustrate, I will refer to the case of terroir in the Republic of Moldova.

So, without referring to any particular parallel, I mention that the small republic across the Prut falls within the northern belt, between parallels 30-50 degrees, where vine growing is developed. Experts are already talking about the fact that, due to global warming, vineyards could be moved further north. But until then, we’ll address the current situation.

Light and heat

Vines are sensitive to light, temperature and humidity. Thanks to light, the most important process – photosynthesis – takes place in the plant. Excessive or insufficient light therefore damages the normal development of the plant. With this in mind, when setting up a vineyard, winegrowers should observe a few basic rules: optimal distance between rows, avoid planting trees in close proximity to the vineyard, even 10 m from the last row of vines.

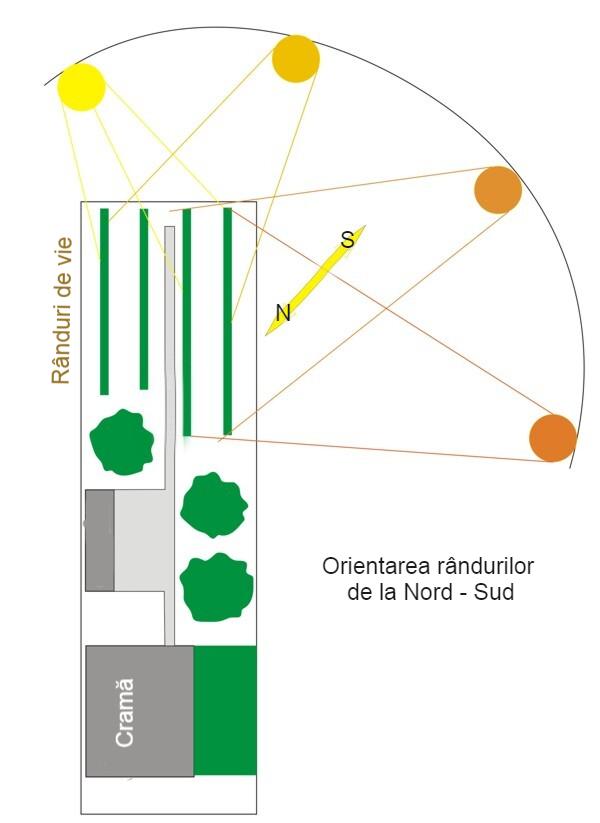

Obviously, there are exceptions. In areas with very strong winds, trees can be planted closer to the vineyard. The rows should be orientated from north to south so that all the plants can enjoy light and warmth throughout the day. In the absence of light, leaves and shoots turn yellow or the grapes are late to ripen.

Note that the orientation of the rows depends on the geographical position and the prevailing winds which must blow parallel to the rows.

Sufficient light and warmth help to build up the necessary amount of sugar in the berries.

The impact of temperatures

When it comes to temperatures, we draw attention to the sum of the active temperatures required for the ripening of the plant and, effectively, the grapes. Thus, a certain sum of active temperatures is recorded over a period of time. This period begins in spring, when the air temperature, but especially the soil temperature, reaches 8-10°C, and ends in late autumn, when temperatures reach the same values. It is at 8-10°C that the vine wakes up after the resting period and continues with the growing season. Depending on varieties and microclimates, the amount of active temperatures can vary. For example, for full maturity, some early and table varieties need a sum of 1450 – 2600 °C, others – over 4000 °C.

Other useful information on the influence of temperatures on vines: the eyes begin to develop at 10-12°C. At 20°C the vine will grow rapidly accumulating sugar and the acidity will decrease.

The optimum ripening temperature for berries is 28-32°C. At temperatures below 16°C the grapes ripen slowly. To flower, vines need 14-18°C, max. 23-25°C. If the plant is in flower and temperatures drop to 14 °C, there is a risk that normal pollination of the flowers will not take place. Similarly, low or even negative temperatures during the grape harvest can cause damage because the grapes can no longer be processed. Another important aspect is the exchange of day and night temperatures. High temperatures during the day and cooler temperatures at night favor a balance between sugar and acidity in the berries.

Temperature and humidity create a microclimate in the soil that is very important for root development. However, its temperature depends both on its colour and on the air temperature at a height of 15 m above it. How does this affect the vines? The heat causes chemical reactions in the soil that feed the plant. Depending on their nature, under the influence of heat, minerals circulate vertically and horizontally, so that the root gets sufficient nourishment. Similarly, if the air temperature is extremely high, the moisture in the soil, which is especially necessary during the plant’s growing season, is reduced.

Rainfall and humidity

Relative air and soil humidity are natural factors that contribute to normal vine development. Furthermore, studies have shown that some red varieties on soils with relative humidity are more intense in colour. Light rains are necessary for the plant, especially when it is in flower. However, frequent rains during flowering prevent pollination. Droughts in summer weaken the vine and prevent it from preparing for winter. That’s why autumn rains are welcome for vines.

In winter, rainfall in the form of snow increases the soil’s ability to accumulate moisture and protects the plant from frost. For example, a 5 cm layer of snow increases the temperature by 4 degrees and a 20 cm layer of snow protects the soil from frost.

Depending on their nature, under the influence of heat, minerals circulate vertically and horizontally, so that the root gets sufficient nourishment. Similarly, if the air temperature is extremely high, the moisture in the soil, which is especially necessary during the plant’s growing season, is reduced.

Slopes, exposures and altitudes

As a rule, more heat and light gather on slopes. Research has shown that the roots of some grape varieties grow much better on slopes than at their base. For example, on slopes, roots can grow to depths of 4-5 m, whereas at the bottom of slopes, where it is cooler and less hot, roots can only reach 180 cm.

For the most part, growers avoid planting vines near steep slopes and choose plateaus with open slopes, preferably 2 – 6°, maximum 10°. Why? Firstly, because of the high slopes. Cold air from the high ground descends into the depressions and the cold stays there. The phenomenon is called ‘thermal inversion’. Because of the lack of heat, planting vines in such places is not recommended.

The greater the slope angle, the more costly and problematic vineyard maintenance can become. In such cases, a certain layout of the plots should be chosen so that the vines can benefit from warmth and light.

What happens in Moldova with slopes over 15 degrees? Firstly, it increases the intensity of erosion, which in turn leads to the degradation of the entire soil genetic profile due to water and surface run-off. In order to slow down the erosion process, depending on the degree of slope, various weeds are allowed to grow between the rows of vines. In this way, the plants will help the vineyard from being ‘washed away’ by surface water.

Secondly, on such slopes, vineyards should be planted to a length of no more than 10 m. For example, only 4-5 rows of vines can be planted on a single plot – which makes it difficult to use means of transport (tractors) both for harvesting the grapes and for loosening the soil.

Slope exposure involves the orientation of a landform in relation to its exposure to the sun. Depending on the angle of inclination, a certain amount of sunlight accumulates on the slope.

In Moldova there are two types of slopes: warm – southern, south-western, western, south-eastern; and cold – northern, north-eastern, north-western, and eastern.

When we speak of altitudes we refer to the peaks above sea level. Depending on the season, the higher you go, the more you climb, the more the temperature drops by 4-8 °C. For example, vineyards in the south of Moldavia at high altitudes, with southern exposures, will give good results. Conversely, at higher altitudes, northern slopes are destructive to the vineyard.

Other natural factors

I will list them one by one. Water resources near a wine-growing region or vineyard help to maintain relative humidity and protect against frost. Forests, likewise, conserve moisture, protect vines from strong winds. Mesofauna – insects and micro-organisms that ‘drill’ into the soil to allow air to penetrate. Likewise, micro-organisms on grape berries contribute to the fermentation process.

Human involvement

Complex, maybe even personalised. It involves:

- work in the vineyard, whatever the season;

- arranging terraces according to the angle of inclination;

- measures to prevent erosion or diseases and pests;

- the affinity/matching of a noble variety and rootstock;

- choice of cuttings of suitable length for planting;

- hygiene at the winery;

- he winemaker’s personal style of creating quality wine.

All this and more is part of terroir.

I will discuss the role of soil as part of terroir in the next article. I will also leave a link to an article about Romanian terroir written by my colleague Emil.

Selected Bibliography:

- Ungurean, Solul și strugurele. Editura Știința. Chișinău, 1979;

- Zemshman, Solul. Clima și strugurele. Chișinău, 2000;

- Cuharschii M.S., Călăuza viticultorului. Editura Cartea Moldovenească, Chișinău, 1983;

- Rubanov L.I, Microraionarea soiurilor de viță de vie din Moldova. Editura Știința. s.l., 1983;

- Morozova, S., Viticultura. Bazele ampelografiei. Moscova, 1987;

- http://vinogradgid.ru/kultura-vinograda/napravlenie-ryadov.html

- https://www.vitisphere.com/actualite-68837-Les-pistes-possibles-pour-adapter-le-vignoble.htm